20.4.2 Horizontal Curves (Specific)

Transportation agencies in the United States typically use circular curves at roadway horizontal curve transition locations. A motorcyclist adapts to the roadway curvature by reducing speed upon entry to the curve. This speed change is often accompanied by a path correction where the motorcycle may enter the curve on the outside of a travel lane, shift to the inside of the lane as the vehicle traverses the curve, and then return to the outside of the lane as the vehicle exits the curve. This path correction often occurs at the same time as the motorcycle accelerates for the length of the curve. Drivers of four-wheel vehicles make similar adjustments to their travel path.

Horizontal curves where the radii values are less than 500-ft are 40 times more likely to have motorcycle-to-barrier crashes than when the radii are 2,800-ft or greater.

Horizontal curves with a radius of 820-ft or less can expected to increase crash frequency by a factor of 10.

Locations with identical radii, roadways with longer curves, larger AADT values, and isolated curve configurations (i.e., curves not located within 300-ft of another curve end) are stronger candidates for the placement of motorcycle-tobarrier crash countermeasures.

When compared with flat curves (radius greater than or equal to 4,000-ft), sharp curves with a radius less than 1,500-ft could be expected to increase the probability of a fatal or serious injury crash by approximately 8 percent. Moderate curves did not have any significant trend. Locations with reverse curves were affiliated with an increase of approximately 6 percent in fatal or serious injury crashes.

Risk for single-motorcycle crashes decreased as the horizontal curve radius increased. This equated to a motorcyclist having almost five times the risk of a crash on horizontal curves with a radius of 1,500-ft or less compared to risk on a similar road with a straight section. This amount reduced to about two times the risk for moderate curve radii (greater than 1,500-ft but less than or equal to 3,000-ft). For flatter curves with radii greater than 3,000-ft, the risk was 1.88 times that observed for a straight roadway segment. Researchers define a straight segment as one with a radius greater than 20,000-ft.

The placement of reverse curves resulted in more crashes than at locations without reverse curvature. This observation reversed the findings from the 2017 study by the same core group of authors. The authors hypothesized that this reversal was due to inclusion of an interaction term in the statistical model that accounted for curve radius as well as curve type.

Higher speed limit and presence of auxiliary lanes and intersections were all associated with higher crash frequencies. The researchers also determined that paved roads and shoulders were associated with higher speeds and therefore increased the likelihood of crashes. In contrast, they observed that narrower roads tended to be associated with fewer crashes. The researchers hypothesized that this observation may be because narrower roads tend to be lower-performing local roads and more riders on these facilities may be local riders who are familiar with the narrower road.

Crash Modification Factors for Motorcycles:

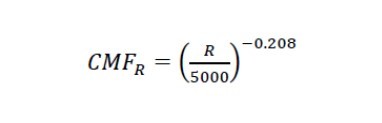

General equation except for rural two-lane:

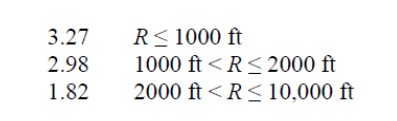

Empirical CMFs specific to rural two-lane: